A burst in biological change among Australian sea snakes has perfectly supported hard-to-prove theories predicting rapid but sporadic “pulses” in evolution.

The international research team’s paper, which is co-authored by South Australian Museum evolutionary biologist Dr Mike Lee, has been published in Evolution, the respected International Journal of Organic Evolution.

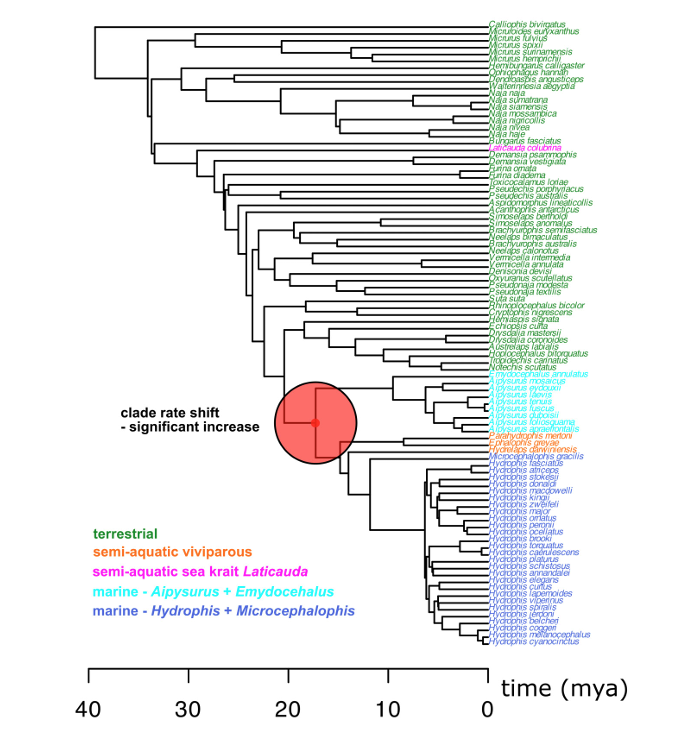

The paper studied Australia’s sea snakes, which split off from our terrestrial venomous snakes or elapids, about 17 million years ago. Elapids include species such as tiger snakes and taipans, and arrived in Australia less than 40 million years ago.

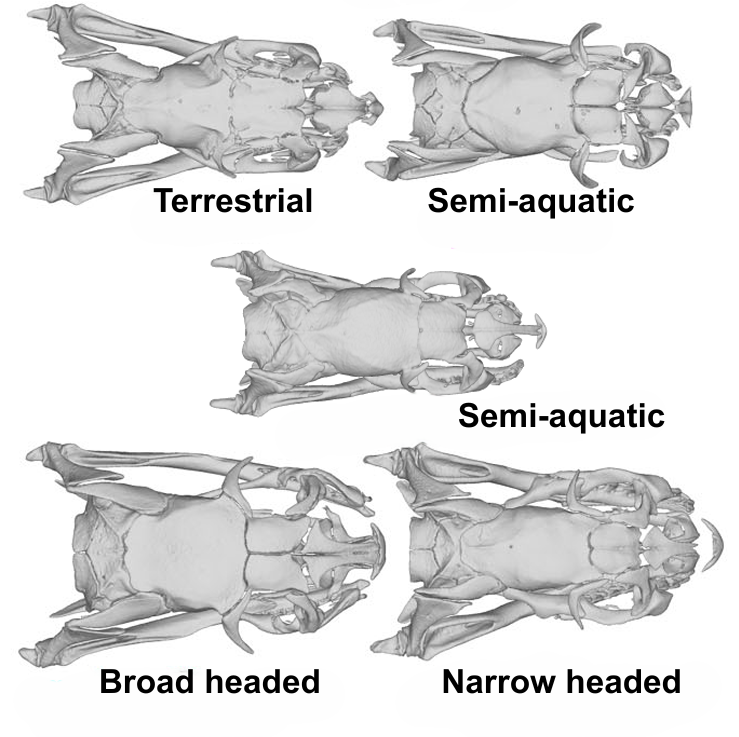

Soon after entering the water, sea snakes rapidly diverged into two groups or clades, which repeatedly evolved narrow and broad-headed varieties as they sought out new niches in the marine environment.

Dr Lee, who is based in the South Australian Museum’s world-renowned Science Centre in the North Terrace cultural precinct, said the Museum’s collection of sea snake specimens was crucial to the research.

Dr Lee can be seen above with examples of both narrow and broad-headed sea snake specimens.

“A single species went into the water,” he said. “And it soon split into two lineages which started developing different head shapes; one wide and flat, one narrow and deep, which were alternative solutions for streamlining.

“The narrow-headed group Hydrophis soon adapted to forage for food in tight spaces and then repeatedly evolved tiny-headed forms to probe eel burrows, while the broad-head Aipysurus group soon adapted to hunt wide prey and then repeatedly evolved chunky-headed forms to swallow large fish.

“It was a subtle change at first, but pretty much dictated the evolutionary future for both groups. It’s like entering a freeway – you can’t turn around very easily.”

The skulls also developed upgraded sensory organs better suited to a life in water.

Theory proposes that much of the world’s biodiversity may be attributed to “pulses” of rapid evolution, as seen by the research team in the two groups of sea snake.

“It’s a common idea often mentioned text books,” Dr Lee said of pulse evolution, “but there are surprisingly few well-documented examples.

“Quite often we don’t have good fossils showing the transition, or we don't know enough information about relationships and anatomy of living forms to project back in time.

“But our study shows that when the sea snakes lineage moved into the water, it immediately started evolving much more rapidly and we’ve captured that transition perfectly in this research.”

Dr Lee said the transition probably occurred in less than a million years.

“It sounds like a long time,” he said, “but from an evolutionary perspective it happened quite quickly.”

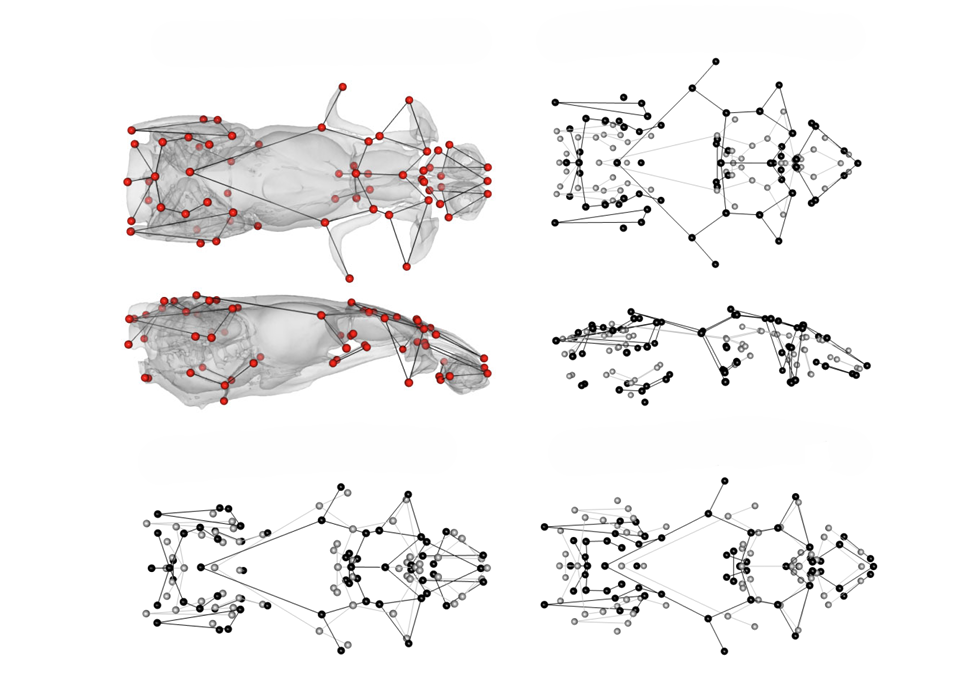

The research team led by evolutionary biologist Associate Professor Emma Sherratt at Adelaide University studied 220 specimens from 91 terrestrial, amphibious and fully marine elapid species using X-ray computed tomography and geometric morphometrics – measuring the distance between key characteristics in their skulls.

Specimens came from ethanol-preserved collections at natural history museums in Australia, US, UK, Denmark, and Indonesia, including the South Australian Museum's large Biological Sciences Collection.

According to the paper in Evolution, ‘ecological opportunity’ is often used to explain rapid evolution when organisms enter anew environment.

“Rapid evolution is most commonly observed in young clades [and] the relatively young age of the sea snake clade (15–20 myo) contributes to their faster rates of skull evolution," the research team said in the paper.

You can read the full scientific paper, titled Rapid evolution and cranial morphospace expansion during the terrestrial to marine transition in elapid snakes, in Evolution.