It had all the makings of a wonderful, big-budget cinematic blockbuster.

An esteemed Japanese professor undertakes a dangerous expedition in 1939 to the jungles of a remote Pacific island to investigate reports of fantastic beasts.

He’s then followed decades later by a team of adventurers and a researcher from the South Australian Museum, who meticulously tracked his footsteps through tropical forests and up mountains to reveal the creatures in all their spectacular glory for a modern world.

Except the amazing creatures discovered by Professor Teizo Esaki from Kyushu University just before WWII were, well, really quite tiny.

Amazingly colourful and interesting, but tiny.

Still, not wanting to ruin a good story - the beasts in question are called ‘giant’ springtails after all, and they’re hexapods from the class “Collembola” – so think ‘six legs’ but not an insect.

Giant springtails can be up to 17mm long, compared to smaller varieties which measure less than 1mm in length.

Prof. Esaki collected the first invertebrate specimens during his expedition in July 1939 to Pohnpei, formerly part of the Caroline Islands known as Ascension, then Ponape, and now one of the four island states in the Federated States of Micronesia.

This first collection contained an endemic new species of Collembola described in 1944 by his colleague Dr. Hajime Uchida (University of Hirosaki) that is now known as Uchidanura esakii.

Dr Mark Stevens, Senior Research Scientist at the South Australian Museum, said that specimens of this species were hard to come by but were now necessary more than ever to resolve decades of taxonomic classification uncertainty.

“The problem was that the genus Uchidanura is known as the ‘TYPE’ for the subfamily Uchidanurinae that unites a group of eight genera across India, Vietnam, Malaysia, Micronesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand and Australia.”

“A new expedition to Pohnpei to collect specimens was the only solution” he said.

Dr Stevens followed in Prof. Esaki’s footsteps to the island with members of the Waterhouse Club.

Re-collecting from Pohnpei was crucial to be able to build the best picture of the group by combining the taxonomy with molecular data for these incredibly diverse animals.

This is a study he has been working towards for the best part of 25 years with his colleague Dr Cyrille D’Haese from the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris.

“These giant Collembola are truly spectacular,” Dr Stevens said. “They are the largest recorded globally and many are brightly coloured with digitations or finger-like projections on their body.

“But the morphological traits that are used to define taxonomic groups in Collembola are generally difficult to work with in this group and many are lacking the furcula or the spring-organ, which may seem odd for a group commonly known as ‘springtails’.”

Dr Stevens traveled to Pohnpei in 2014 with funding from the Waterhouse Club, which was founded in 1987. Members support Museum researchers and often travel with them on field trips.

His new research paper with Dr D’Haese titled Fantastic beasts: ‘giant’ springtails(Collembola) highlight convergent evolution and major changes in the superfamily Neanuroidea, has just been published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, along with a companion-piece in The Conversation.

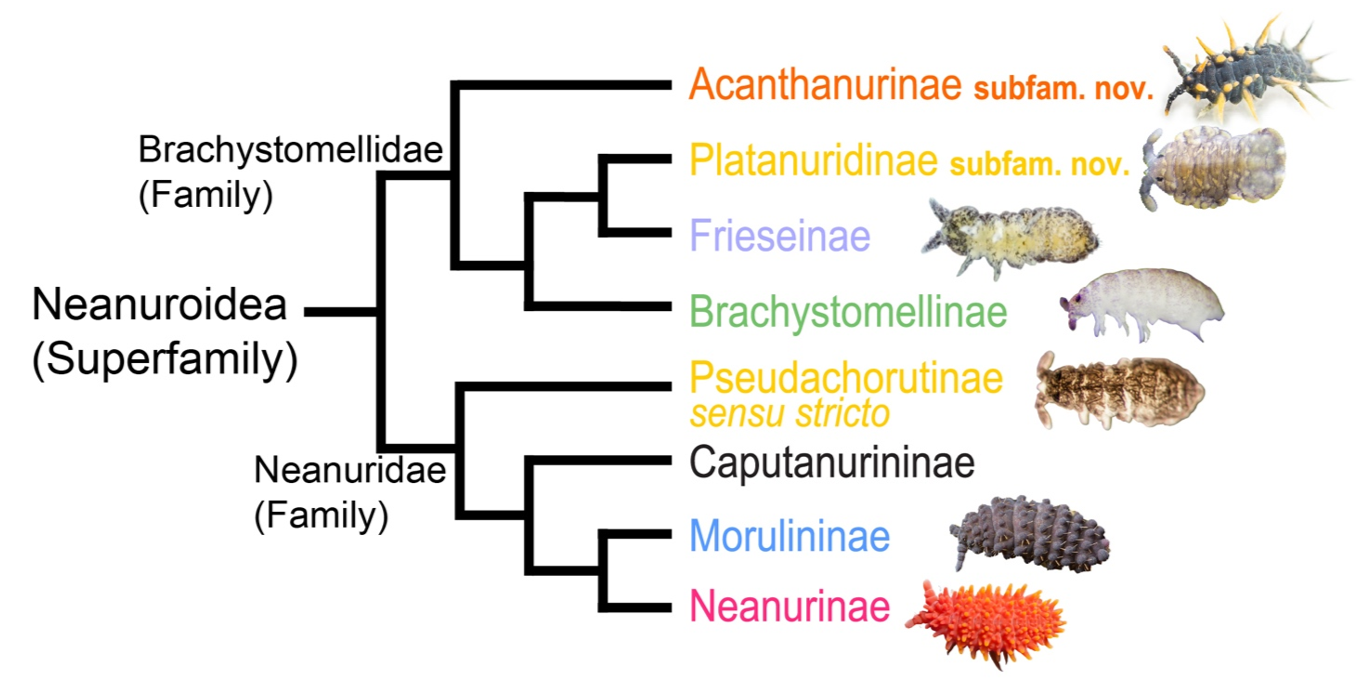

In the research paper Drs Stevens and D’Haese showed that the subfamily Uchidanurinae was not valid. They dissolved it and reclassified the superfamily by re-assigning the two families Brachystomellidae and Neanuridae, created two new subfamilies, and dramatically changed two others.

“We could not have undertaken this investigation without re-collecting Uchidanura from Pohnpei,” Dr Stevens said. “This was critical for us to examine the subfamily Uchidanurinae with both morphological and molecular data as is now commonplace for modern taxonomy, but we were also able to do so much more from our extensive collection.”

The team also discovered there was a distinct divide within the group between those found in the northern and southern hemispheres. The two new subfamilies (Acanthanurinae and Platanuridae) were identified as largely southern hemisphere ‘Gondwanan relictual’ species.

“This is the first study we are aware of that reveals such a split between hemispheres within any family of Collembola,” Dr Stevens said.

“It has the potential to ignite new research to shed light on geographical and evolutionary hypotheses that have been largely ignored in Collembola.”

Dr Stevens has published numerous studies with Dr D’Haese, and has been working on trying to correctly classify springtails and describe new species including these ‘giants’.

“We have probably lost more than half of these incredible species before they have been given names," he said. "This is a 'silent' mass extinction as environments disappear or become unsuitable.

“This is especially true for these giant springtails that are now critically threatened by warming and drying climates in Australia and New Zealand. They are an under-appreciated fauna but are the ‘canaries in the undergrowth’ as indicators of the health of our forests that we just need to stop ignoring.”

Read more about these fantastic springtails and the study by Drs Stevens and D’Haese in The Conversation.

Follow the link for more information about the Museum’s collection of terrestrial invertebrates.

Read about Dr Herbert Womersley on the South Australian Museum’s website.