Renowned South Australian Museum researcher Jim Gehling AO has received one of the state’s most prestigious science awards, for his contributions to the scientific community.

Dr Gehling (above), 79, who retired from the Museum in 2017, was last night (Thursday 9 October) presented the Royal Society of South Australia’s Verco Medal.

The medal is awarded to those the society recognises as having made an outstanding contribution to their field.

Previous winners include Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson and Reg Sprigg, who discovered the 555-million-year-old Ediacaran fossils in the Flinders Ranges in 1946.

Dr Gehling, who describes himself as a sedimentologist, continued that work - first as an undergraduate volunteer for University of Adelaide’s Prof. Martin Glaessner and Dr Mary Wade, then through his Masters, PhD and lecturing years for the College of Advanced Education, later University of South Australia.

He joined the Museum in 2003.

In 2005, Dr Gehling was instrumental in the formal naming of the Ediacaran Period, covering an interval from approximately 630 million to 542 million years ago.

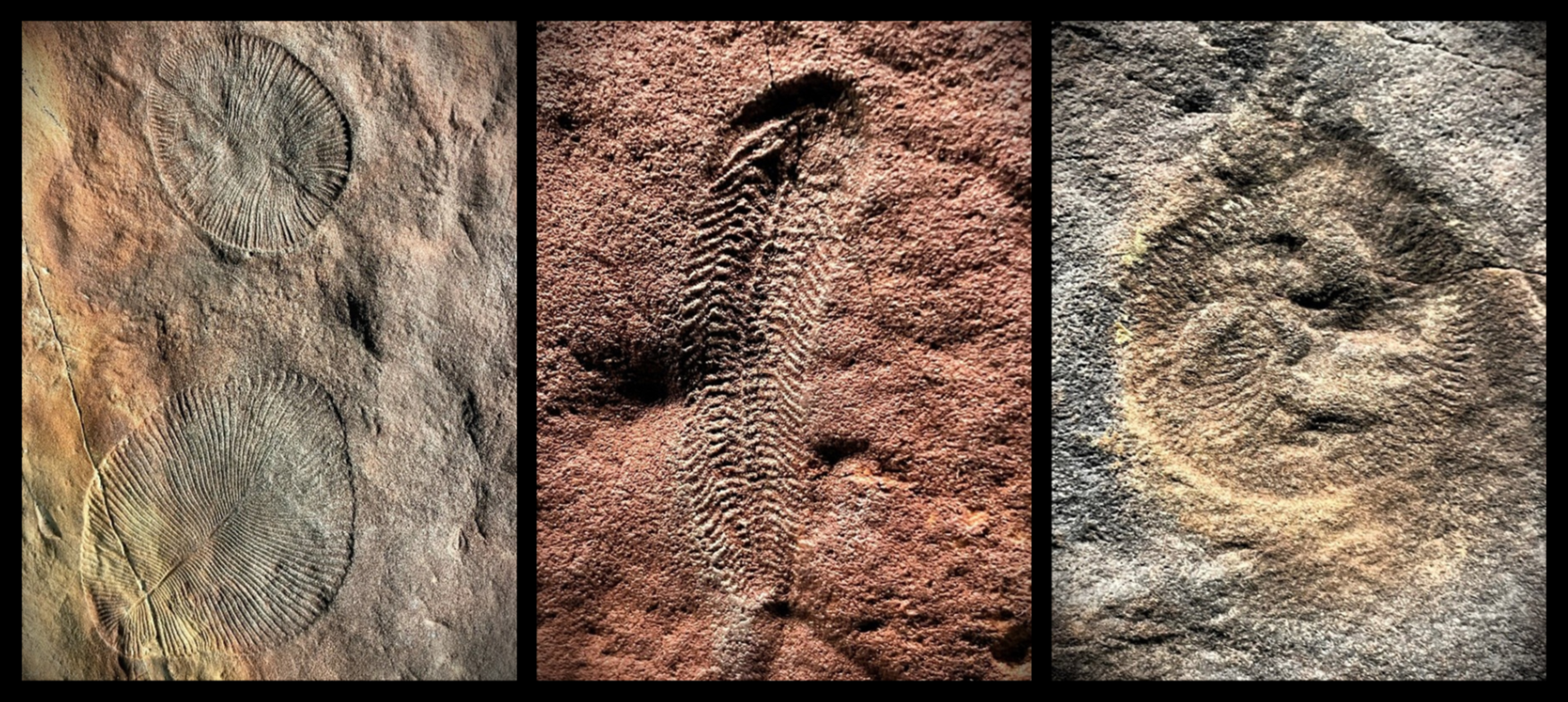

The Ediacaran fossils captured the moment when life developed from simple single-celled organisms that mostly grew in mats on the sea floor, to more complex lifeforms that moved about under their own steam.

Dr Gehling also worked around the world broadening our understanding of Precambrian fossils, particularly the Ediacaran.

“As humans we have a very short history compared to geological history,” he said.

“So South Australia is very lucky. We can look at the first complex animals – we sit in a critical part of the calendar of life.”

Dr Gehling, who was nominated for the Verco Medal by his successor at the Museum Assoc. Prof. Diego García-Bellido and Palaeontology Collection Manager Dr Mary-Anne Binnie, simply started out trying to learn what had happened in the distant past, and stressed fossils were crucial in understanding what the ancient environment was like.

“The first thing to find out is just how different life was on Earth,” he said. “To use the geological evidence to understand how the Earth has changed.

“Our task is to use the evidence, whether that is footprints or drag marks in the sediment, to the impressions of the animals left behind.”

.jpeg)

Dr Gehling said the rocks found in the Ediacaran fossil fields preserve some of the oldest complex life in the world, and the organisms found there may include the ancestors to most animals on Earth today.

But he insisted the South Australian Ediacaran fossils could not be studied in isolation, and he travelled the world in search of more evidence.

That included Russia and China during the Cold War, Namibia, Newfoundland in Canada, Nevada in the United States and the United Kingdom.

One of the most satisfying aspects of his research, he said, was learning from the researchers he met on those travels – who often had very different views to his own.

“You’ve got to work with people around the world,” he said. “It’s a truly global thing.

“It’s about the people – people approach the evidence indifferent ways; we’re human beings after all.

“There’s no point in complaining about people’s differences; those differences help you re-think your own biases.”

Dr Gehling is philosophical about his legacy, now that he is retired.

“I was just a small cog in the whole business,” he said. “This is a collaborative enterprise, and we learn from each other.

“I’m hoping people will continue to critique what we did.

“That’s science.”

You can read more about Dr Gehling on his Wikipedia page.

Follow the link to read more about some of the Museum’s latest research on the Ediacaran fossil beds.