An unlikely and long-forgotten theft of hundreds of precious butterflies by a ‘gentleman adventurer’ is still being felt by the South Australian Museum almost 80 years later.

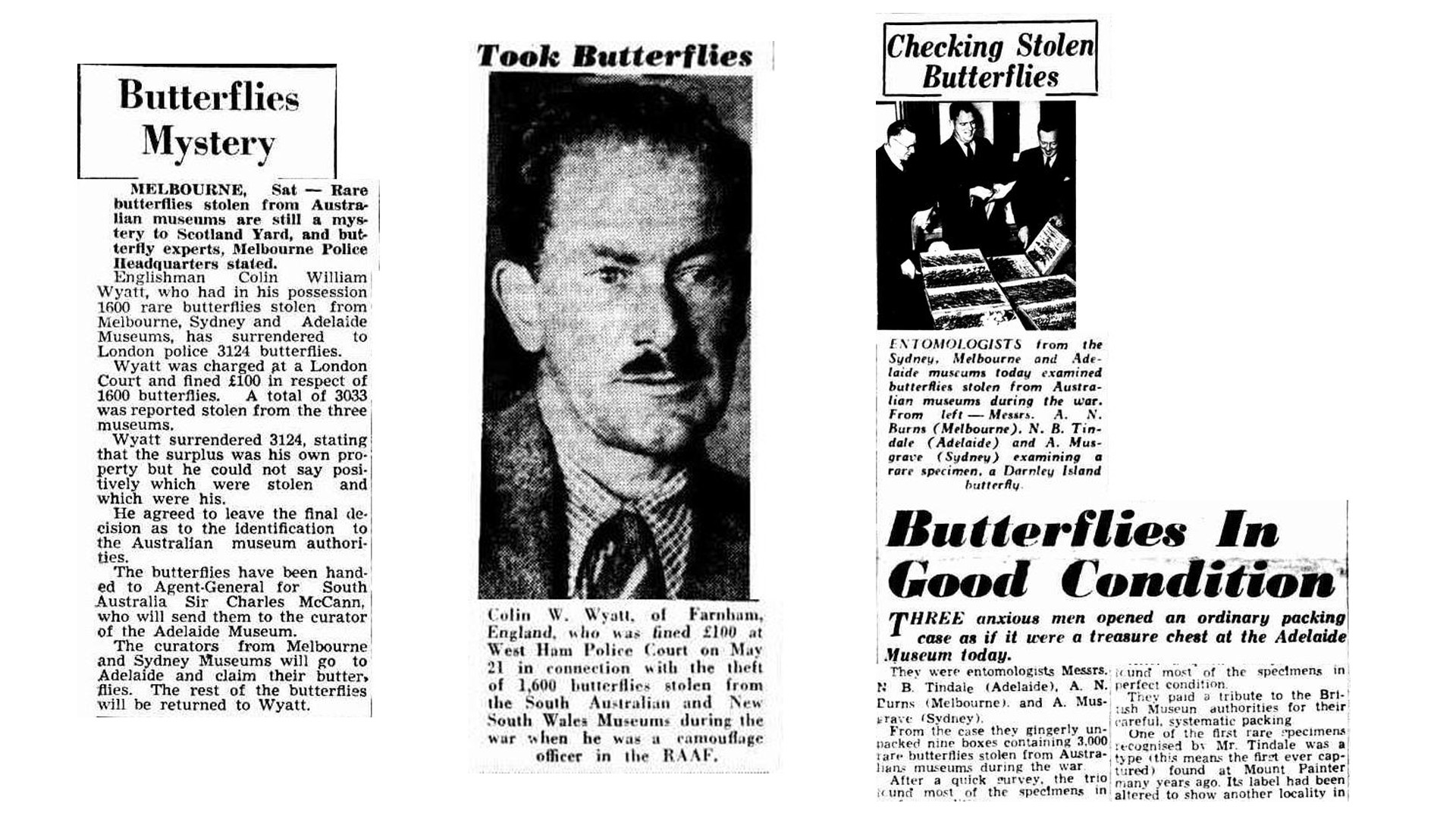

The butterflies went missing from the Museum early in 1947 and were eventually found in far-away England, in the Surry home of mountaineer and amateur naturalist Colin Wyatt.

When police raided the home, they found tens of thousands of butterflies including 3,000 stolen from museums in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Others had been taken from institutions in the US and Europe.

The thefts and subsequent detective story are the subject of a new book The Butterfly Thief by Adelaide author Walter Marsh.

Most of the 600 butterflies stolen from Adelaide, including scientifically precious holotypes that provide the crucial taxonomic reference points for newly described species, were eventually returned.

But as South Australian Museum entomologist Ben Parslow said, each will carry a scientific stigma associated with the theft.

Dr Parslow (pictured top left) is Collection Manager for Terrestrial Invertebrates at the Museum.

“Every stolen butterfly is now under question because Wyatt tampered with them so much,” Dr Parslow said. “But I guess it’s also now part of their history.

“Some of the butterflies got mixed up, and there is now some material that we’re not sure where it is. And researchers now have to be careful when studying the material.”

Wyatt eventually pleaded guilty in court and was fined £100. He died in a plane crash in 1975 while on an expedition to Guatemala.

After the butterflies were returned to Australia, museum curators had to spend years sorting through the butterflies to make sure they were correctly labelled and returned to the right museums.

One of the holotypes in Sydney, initially believed untouched by the scam, was infamously found to be a painted forgery to hide the theft.

Nowadays the South Australian butterflies have been returned to their rightful locations among the many thousands in the Museum’s collection.

Each has a yellow label, “Passed through C.W. Wyatt Theft Coll. 1946-1947”, to warn researchers and collection managers that everything may not be as it seems.

At least one precious Type – the male Bright Forest-blue (Pseudodipsas cephenes Hewitson) didn’t make it back.

Stuck to its vacant pin next to the female specimen, is a tiny handwritten label that says “not returned”.

In a sign of the times it appears Wyatt, who was known to be a gentleman and a naturalist, was allowed to roam unfettered through the Museum’s collection on a visit to Australia. There was no official record of his visit to Adelaide.

An unlocked door led to the suspicion that Wyatt hid inside the museum overnight, and let himself out after several hours of meticulous butterfly ‘collection’.

Dr Parslow said he could not understand Wyatt’s motivations. “To me it’s crazy,” he said. “You are stealing scientific types for a personal collection.

“The scientific value is huge but you can’t show them to anyone – everyone will know they’re stolen.”

Shastra Henry (pictured top right), who is also a Collection Manager of Terrestrial Invertebrates at the Museum, said the theft was akin to stealing a precious and famous artwork.

She noted that Wyatt argued in his defence that the breakdown of his marriage had created mental health problems.

“I can see where the mania comes from,” she said of Wyatt’s hoarding. “He (Wyatt) would be thinking ‘nobody cares about them as much as I do … they’re mine’.

“Pinned and preserved insect specimens can last for hundreds of years if they’re handled carefully.

“The South Australian Museum has specimens collected in 1858 – 167 years ago. The oldest known insect specimen happens to be a butterfly in England which is currently 322 years old.

“So. the legacy of the C. W. Wyatt Theft Collection will be as enduring as his beloved butterflies, for many decades to come.”

And so will some of the mysteries.

“To be honest, I was surprised how many butterflies were stolen,” Dr Parslow said. “How he managed to get them out of the Museum?”

Dr Henry agreed.

“You can’t put a thousand butterflies in your pocket!” she said.

Follow the link to learn more about the Museum’s Terrestrial Invertebrates collection.